The Venerable Thich Quang Duc: The Burning Monk

WARNING: graphic pictures ahead! Don’t say I didn’t warn you!

For the past year, I’ve been driving past a statue of Buddha in District 1 of Ho Chi Minh City. Every time, I see him, I say “Hi Buddha” and he never says hi back (#rude).The statue seems a little out of place, since it’s way bigger than any other statue in the city. But I’m so busy with important things (I have a very important life), so I don’t notice.

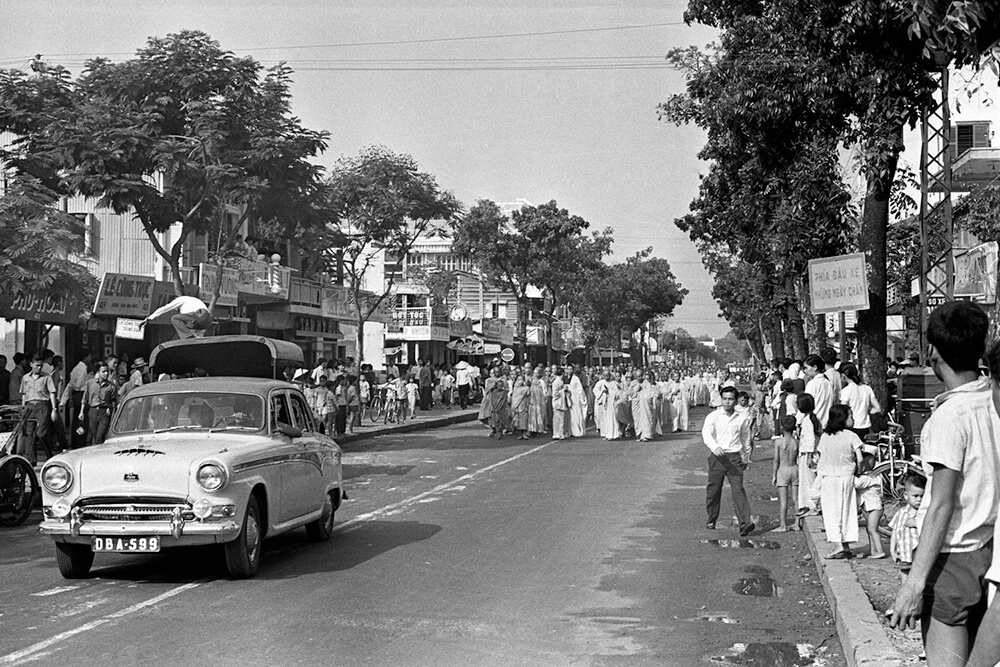

an intersection in HCMC, with motorbikes driving through during the afternoon. Site of Thich Quang Duc’s immolation.

That is, until I realized that statue is none other than the image of Thích Quảng Đức! If the name sounds unfamiliar, you might recognize him from his latest work:

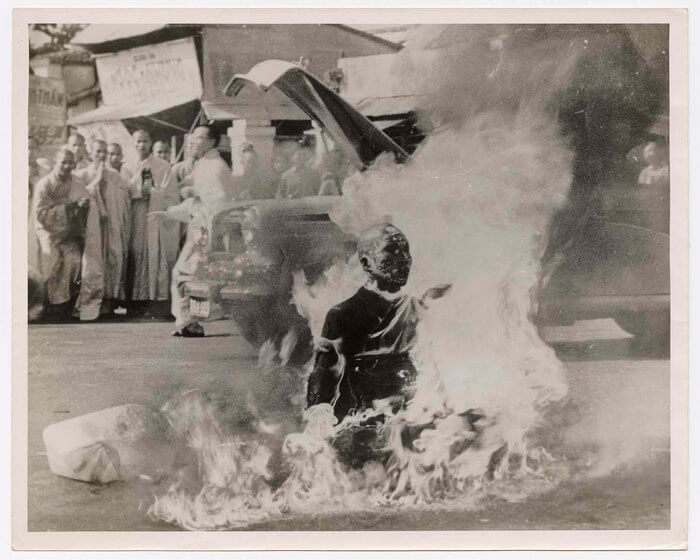

I call it, “On Fire But Okay With That”

Yes! For so long, I’d been passing over the very spot where, one summer day back in 1963, the famous Buddhist monk set himself on fire. (By the way, my photo is taken in almost the same spot as Malcome Browne’s famous one. Only took me 2 hours to figure that out)

The big “wh-” question words are why, how, and where?

Why would anyone in their right mind choose to burn alive?

And

How can someone just sit there as they cook to death?

And

Where do I get his outfit?

Okay, so we’ve got the third question figured out. But to answer the first two, we have to learn a bit about the backstory of the Buddhist Crisis in South Vietnam.

The Birth of South Vietnam

After the Viet Minh defeated the French colonialists in 1954, a Geneva Accord dictated that Vietnam would be divided at the 17th parallel (or as we regular folk say it, “the middle”). This allowed the French to bring their troops back south, and the Viet Minh to bring theirs north.

KKday is a travel APP platform offering over 20,000+ online products such as: tickets for amusement parks, outdoor services, sightseeing tours, culinary experiences, transportation, accommodation, courses, and local culture... Currently, there is a summer promotion with discounts up to 50% and coupons up to 250K VND off.

Attractive discount codes such as: 100K VND off for new accounts, 150K VND off summer promotion, 250K VND off, KKday birthday celebration...

After the French left, they scheduled elections to reunite Vietnam in 1956. The United States, however, hated communism (they had a communist ex-boyfriend, a messy breakup don’t ask about it).

They knew Ho Chi Minh (Uncle Ho) was exceptionally popular after defeating the French, and the elections would result in a fully communist Vietnam.

So the US said “forget your stupid idea, we have a new idea” – Actual quote.

1955 saw the establishment of The First Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam), with a man named Ngô Đình Diệm at it’s head.

“Look you in the eye?? Guess again!!”

Diệm’s government was propped up and funded by the United States. As long as Diệm gave the eternal middle finger to the North, they helped his party win a rigged election to put him in power. They also started fueling the South economy and building up a strong military for “defensive” purposes.

After gaining power, Diệm addressed the nation in his first Presidential Acceptance speech, and said (quote): “It’s Diệm, bitch”.

(Just before a triumphant reading from his Burn Book)

Ngô Family Corruption

Madame Ngo Dinh Nhu. She’s evil too, stay tuned for the details!

The South Vietnamese government immediately became your standard corrupt and vicious tyrannical regime.

They began attacking and executing “suspected communists” using death squads. Diệm hired only family and close cronies to high positions, skimmed off a sizable portion of US funding to fill their own pockets, and restricted freedom of the press.

They implemented social reorganization programs, grabbing people from their villages and moving them into large camps. This was to keep the Communist Influence from spreading (like when your parents make you stay home every weekend so you don’t go around eliminating the bourgeoisie and redistributing the wealth with your friends).

“Mom says I can’t go out today”

The people in these camps were unhappy (go figure!) about being pulled from their ancestral homes. Also, they received plots of land too small to make money farming on (“okay, here’s your farmland, you may grow one (1) corn”).

The only good thing Diệm and his National Assembly (his brothers and sisters) did was help boost the South Vietnamese economy. The US was happy about that, so they looked the other way while he did literally everything else wrong.

The Buddhist Crisis

Diệm was a little fanboy of the West, and his family was Catholic (not many Vietnamese Catholics at the time). He thought he was better than everyone else, especially those good-for-nothing Buddhists. At the time, 70-90% of religious Vietnamese people were Buddhist (almost half!).

Catholics received high positions in the government and military, land ownership, and tax breaks. Buddhists, however, were banned from most celebrations, including flying their religious flags. This ban occurred on the eve of one of the most important Buddhist holidays in 1963.

Buddhist monks were angry about this injustice, since who can deny the raw pleasure derived from a good flag waving? That spring, they staged a peaceful protest in Hue (Central Vietnam).

The Southern military, called the ARVN, saw this peaceful protest, and I guess the conversation went something like this:

“What should we do with the peaceful monk protesters, sir?”

“Are they hurting anyone?”

“Not even a little.”

“Do they have valid concerns about the welfare of their lifestyle?”

“One hundred percent, yes.”

“Have you tried dispersing them non-violently?”

“Not yet, but we have many non-violent ways to diffuse this situation.”

……….

“Shoot them all.”

The ARVN started a relaxed and easygoing blind-firing into the crowd, killing nine people. Several vietnamese people pull on barbed wire while soldiers pull against them

Buddhists around the country heard about the Huế Phật Đản shootings, and staged even more protests; organizing rallies, sit-ins, and hunger strikes.

The explosion of dissent rocked the nation. At the time, however, there wasn’t much international attention to the suffering of the Vietnamese people.

A Buddhist Priest Becomes a Martyr

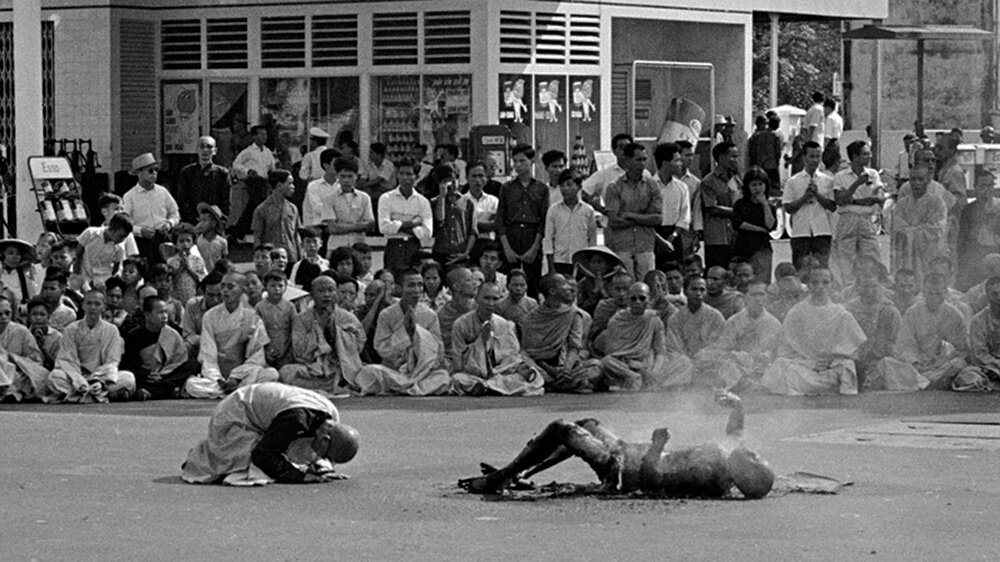

On June 11, 1963, at around 9AM, a 65 year old monk stepped out of a car onto an intersection in District 1 in Saigon. Dozens of walking monks followed. Some members of the American press had arrived. They’d been tipped off the night before about a “big event”.

A circle of marcher and onlookers formed around him. One of the monks spoke over a megaphone, calling for President Diệm to make peace with the Buddhists, and allow them their religious freedom.

A monk carried a jerry can of gasoline towards Quảng Đức, who sat in lotus position on his cushion. They emptied the contents over his head. He turned prayer beads in his hand and recited the words Nam mô A Di Đà Phật (repetition of the name Amitābha). These were to be his last words.

After a short time, he struck a match and dropped it in his lap.

Witness Accounts

A reporter, David Halberstam, said: I was to see that sight again, but once was enough. Flames were coming from a human being; his body was slowly withering and shriveling up, his head blackening and charring. In the air was the smell of burning human flesh; human beings burn surprisingly quickly. Behind me I could hear the sobbing of the Vietnamese who were now gathering. I was too shocked to cry, too confused to take notes or ask questions, too bewildered to even think … As he burned he never moved a muscle, never uttered a sound, his outward composure in sharp contrast to the wailing people around him.”

Malcome Browne, the photographer who took the world-famous photo, noted: “I don’t know exactly when he died because you couldn’t tell from his features or voice or anything. He never yelled out in pain. His face seemed to remain fairly calm until it was so blackened by the flames that you couldn’t make it out anymore.”

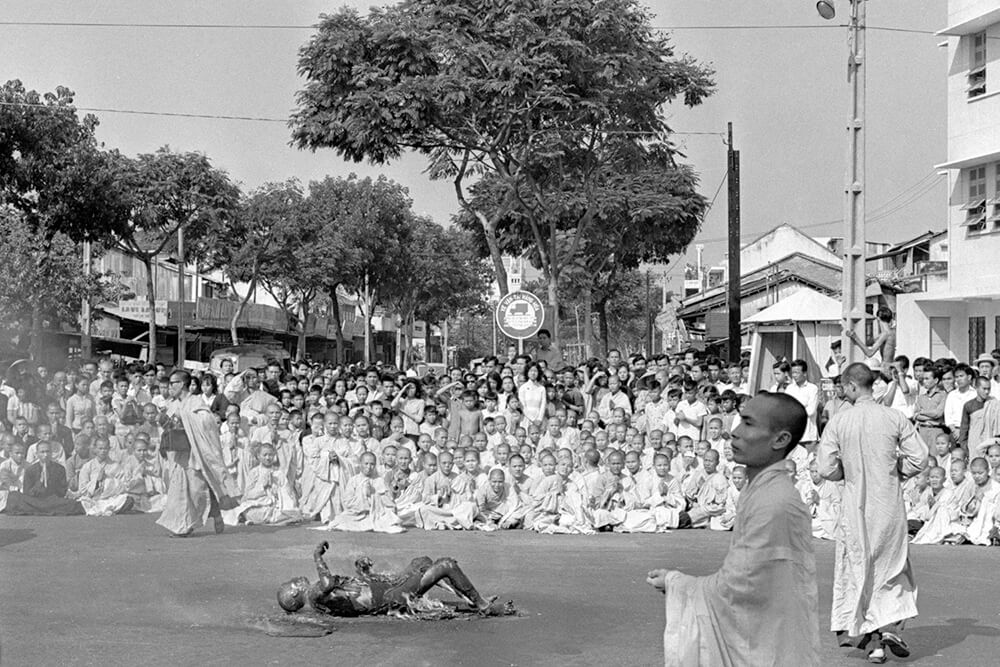

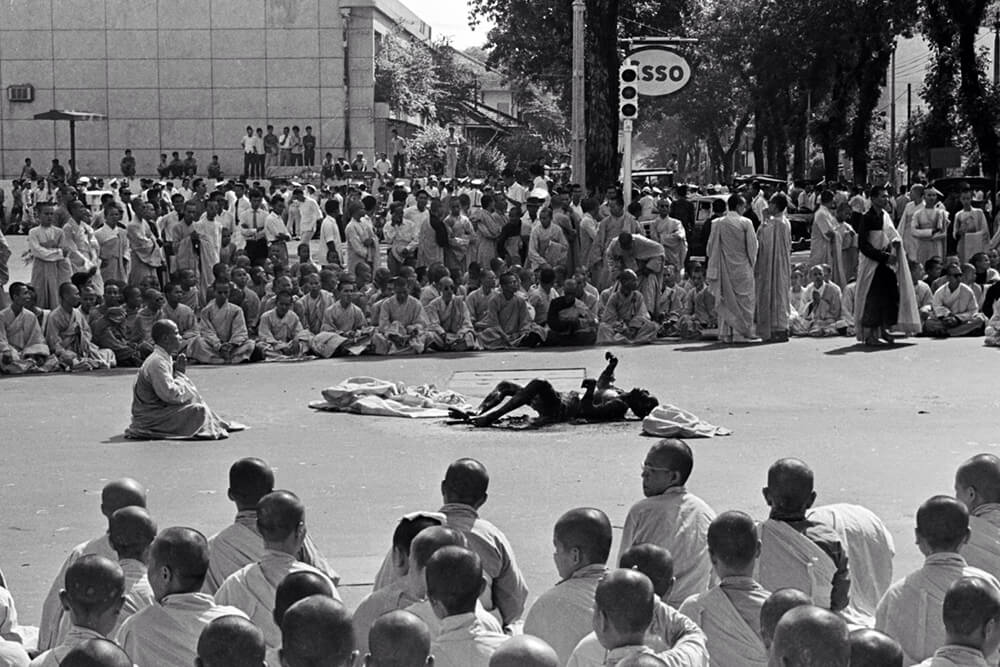

He sat for about 10 minutes while the flames from his body crackled. The monk on the megaphone repeated, “A Buddhist priest burns himself to death. A Buddhist priest becomes a martyr”. Monks, civilians, even police flung themselves down in front of him in prostration.

What Is It Like to Burn to Death?

I think it’s difficult to appreciate the real weight of this event. To me, it’s a poignant example of the limits of human capability. Physically and psychologically. For a greater cause, Quảng Đức put himself through what may be the most painful experience the human body can endure. Not for his family. For strangers. For a belief. To do what’s right. That in itself is exceptional, and uniquely human.

As mentioned above, I introduced the Buddhist monk from the famous Vietnam war photo. Most Americans are familiar with this photo, but let me give you some background information.

Thích Quảng Đức, a 65 year old Vietnamese monk, is burning alive in an intersection in wartime Saigon. It’s to protest the oppression of Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government in the early 1960’s.

When this photo hit the press, it caused an international upheaval.

People were aghast. They knew there were protests in Vietnam. Everyone knew there was some discontent with the government. But not like this.

“How bad could it be over there”, we wondered, “that people were burning alive in the streets?”

The photo immediately caught the attention of the world, as it was intended to.

Almost everyone I’ve talked to about the Saigon monk, and saw his photo, say the same thing: “How could anyone do that?”

We know what it feels like to get burned. For most of us, it was small. But we know even the tiniest burns cause intense, lasting pain.

But when we look at a picture like this one, it’s hard to empathize with someone suffering that much. Our mirror neurons multiply the burn in our imaginations. We can almost feel it covering our entire body, the agony magnified by ten trillion.

We stop, and wrack our brain for a reason he would intentionally burn to death. Because the idea is completely alien to us. Why would anyone choose to suffer like that?

Nobody really comes up with an answer, though. It usually ends with them deciding that Buddhists have some secret power, or that 1963 was the year that “fire doesn’t hurt anyone!”

They figure that there must be some unexplained factor that they’re missing: maybe he was a physically special person, maybe he was dead or dying already, or drugged, or maybe even that fire isn’t very painful after all.

The reality is much worse. A complete, bodily burn is every bit as horrible as you thought it was, and then some more.

Why Does Fire Hurt So Much?

Burns are a unique type of damage. It’s unclear why, but they’re disproportionately more painful than other injuries of the same caliber.

For example, for a slicing injury versus a burn injury of the same size, the burn hurts exponentially worse.

In fact, they’re more painful than even their own level of damage. (Interestingly, the pain from crushing injuries also doesn’t match the level of damage).

Why?

It’s not certain why burns hurt more. There’s a few theories:

- Burning damages larger areas of skin and tissue

- Wherever a burn is present, the surrounding tissue gets “fallout damage”. A third degree burn has a large radius of second and first degree burn surrounding it, compounding the damage, and the pain.

- Nociceptors (pain receptors) rest closer to the skin surface, and thermoreceptors are stimulated in particular by heat.

- Burning releases a cocktail of proteins that aren’t found in other injuries (cytokines and prostaglandins, which sensitize the nerves to pain)

The pain from a burn is, in a very simple sense, unendurable. Biologically unendurable. It’s at the very peak of what a human can tolerate. The nervous system will shut down because it can’t even reason with what’s happening.

Burning is also particularly painful after the fire has been put out. For most, burning provokes “stress-induced analgesia”, which is the release of endorphins and other neurotransmitters from the thalamus, blocking out pain receptors.

The pain builds in the hours afterwards, and remains at a constant high for weeks, depending on the severity of the burns.

Luckily for our monk, he was dead before any of this could happen.

How Does Fire Kill You?

Fire is a versatile monster. It’s incredible how many ways fire can kill a person. And by that, I mean, what happens physically inside your body that will magically transform you into a dead body.

Looking at Thích Quảng Đức and his famous self-immolation, let’s explore all the possible ways he could have died from being set on fire.

Shock

Shock, by definition, is when your body cannot get enough blood or oxygen to all the cells or organs.

There are five types of shock, and fire can cause four of them.

Neurogenic Shock

Let’s start with the first one, called neurogenic shock. This type of shock usually comes from damage to the Central Nervous System (spinal cord or brain). Along with lots of other symptoms, the main thing that happens is that your blood vessels dilate, and your blood pressure drops.

Nobody actually knows why, but fire (even though it doesn’t damage the CNS), can provoke such a strong response in your body that neurogenic shock occurs.

The extreme pain overwhelms your pain receptors and floods your system with information on how the body is “not doing quite well at all, unfortunately”. It’s like every sailor on the ship screaming that we hit the GOD DAMN ICEBURG.

Your CNS shuts off. It lets go of control over automatic bodily functions (like maintaining proper blood vessel dilation). Your blood pressure drops, and you lose consciousness instantaneously.

When Quảng Đức dropped the match into his robes, and the fire whooshed into life around him, it’s possible that the sudden heat rendered him unconscious in seconds.

But I don’t think so. He doesn’t look unconscious in the photos, at least not in the beginning.

Hypovolemic Shock

Fire can also induce a second type of shock, called hypovolemic shock. This is when there simply isn’t enough blood or fluid inside your body to function.

Our skin does a lot more than keep the outside stuff from getting in our body. It also keeps the inside from getting out. When the skin is burned away, fluid escapes through all the raw membranes left behind. This can lead to serious dehydration, and eventually death when you run out of blood. It’s the reason burn victims are so thirsty afterwards, since their body can’t retain the fluids.

What’s worse, in the case of an injury, our body diverts fluid over to the injured area. So, as the burn progresses, the body sends more and more blood and fluid to the site, which drains right out through the damaged tissue.

But losing enough fluid would take between minutes and days, and probably wouldn’t be the primary cause of death for Quảng Đức. He was likely dead around 5 minutes after lighting the match.

The End of a Dynasty

Memorial for Thich Quang Duc. This wall features bronze engravings showing soldiers brutalizing civilians before the monk’s immolation protest.

That single photograph, sent out from the depths of wartime Saigon, shocked the world. Quảng Đức’s immolation solidified domestic international resentment against the South Vietnamese government. It was a critical point in the collapse of Diệm’s regime: the beginning of the end.

Historian Seth jacobs said “no amount of pleading could retrieve Diệm’s reputation”. John Mecklin of the US Embassy mused that it “had a shock effect of incalculable value to the Buddhist cause, becoming a symbol of the state of things in Vietnam.”

John F. Kennedy, President of the US at the time, responded to the photo, saying “no news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one.”

The US government, in the wake of the photo’s backlash, gave Diệm’s regime an ultimatum: make concessions with the Buddhists, or lose US support.

Madame Nhu (remember her?) was flippant (here’s her bit). She called the suicide a “barbecue“, and said, “Let them burn, and we shall clap our hands.” She also offered to bring mustard to the next one, and accused Quảng Đức of being unpatriotic for choosing imported oil.

Diệm, now feeling the pressure, outwardly accepted Buddhist wishes for religious equality. With a few dozens of his highest commanding officers around him, he made a public statement acknowledging Buddhist legitimacy in Vietnam, and promising conciliation.

Secretly, however, he was galvanized to destroy Buddhist opposition. In the weeks after, he planned coordinated attacks on hundreds of pagodas around the country.

The temple where Quang Duc’s body was returned after his death, and the focus of the August Pagoda Raids.

His hit squads carried out the attacks. In the August Xá Lợi Pagoda Raids, they arrested over 1400 Buddhist, and hundreds of people simply “disappeared”.

The Final Nail

Vietnamese people throw bricks and other things through a government building during the South Vietnam government coup

Waiting for the day I get that text: “Wanna go throw bricks through our local government building?”

The overt murder of peaceful religious figures could not be tolerated. Ripples of opposition turned to waves. Diệm’s hold on power slipped away to almost nothing. The people had turned against him, and resentment grew in the ARVN, his own military legion.

The US realized after the burning of the monk that the relationship with the Ngô regime couldn’t be salvaged. Many in the upper echelons spoke about “making changes over there”. Eventually, the US decided to back the military coup that eliminated Diệm and his family.

The coup, headed by his generals, resulted in Ngô Đình Diệm and his younger brother Nhu fleeing their palace after a siege attack. The two were promised safe exile and “honorable retirement” if they gave themselves up without a fight.

After hearing the promises, they surrendered. Unfortunately, the claims were a rouse. The brothers were placed into an armored vehicle, and summarily executed with pistol shots, on November 2, 1963.

Interestingly, the men responsible for the coup were the very same generals who had stood by him during his apology speech after Thích Quảng Đức’s death. At the time of that speech, they had already begun planning his death.

The end of the Ngô Dynasty was prophesied, and maybe sealed, at a Saigon intersection on a summer’s morning.

What did you think? How would you go about overthrowing a government? Tell me your best ideas!